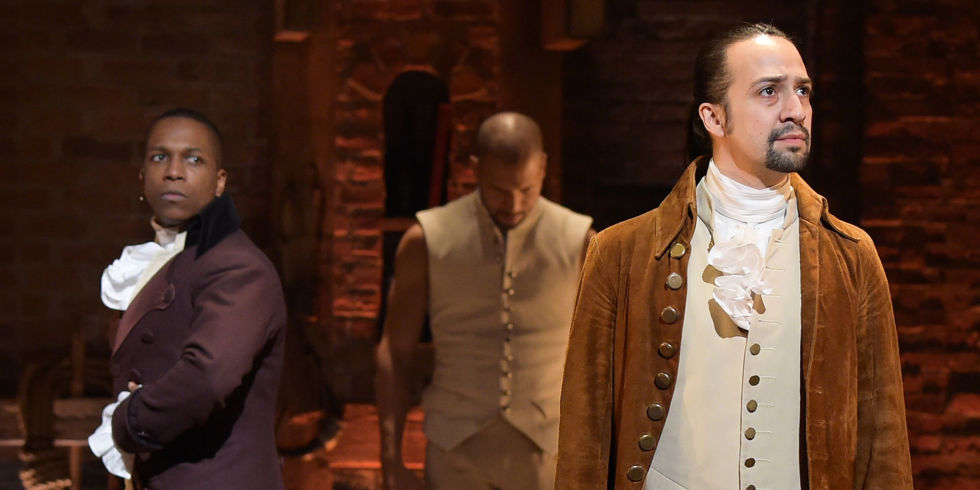

When I was in high school (and this is dating me now), a new ad campaign for milk became the most famous pop-culture reference to Aaron Burr:

But now, with the popularity of the Hamilton musical, more young people know more about Aaron Burr than at any other time in recent memory.

At the age of 45, Burr became the third Vice President of the United States (1801–1805), serving under President Thomas Jefferson. But in 1804, he became most famous for being the first sitting Vice President to shoot someone while in office (Dick Cheney was the second!), the only one to do so intentionally, and the only one to kill the person he shot. That person, of course, was Alexander Hamilton, who was mortally wounded from the duel and died the following day.

In 1758, Aaron’s mother wrote to a friend about her two-year-old son, describing him as “a little dirty Noisy Boy . . . very sly and mischievous . . . not so good tempered. He is very resolute and requires a good Governor to bring him to terms.”

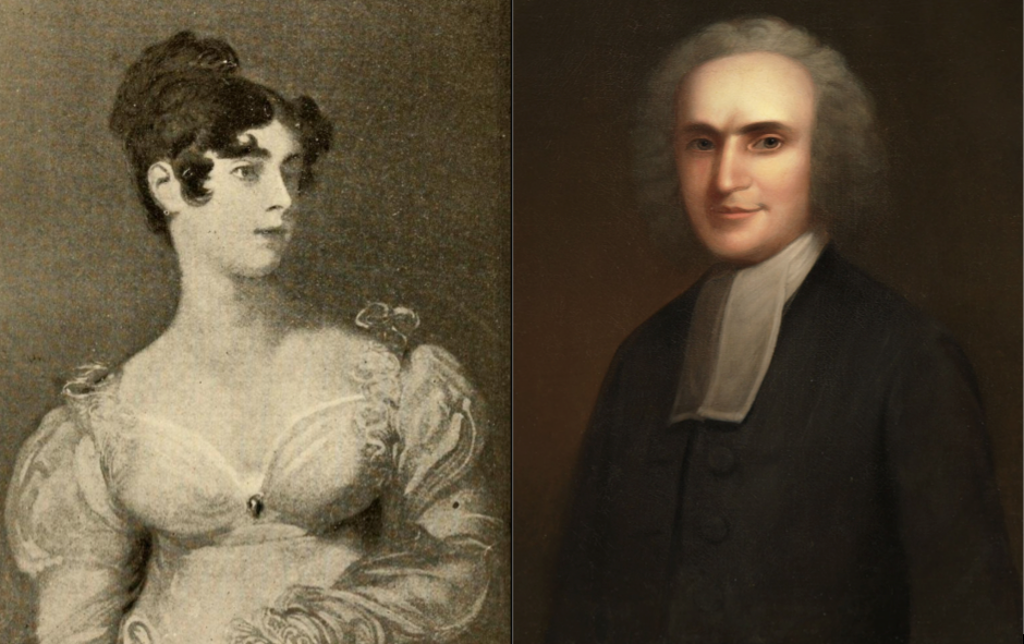

Esther Burr (1732–1758) and Aaron Burr Sr. (1716–1757)

When Burr was still a toddler, a series of deaths struck his family.

He was only 19 months old when his father (Aaron Burr Sr., a Presbyterian minister who founded the College of New Jersey [later Princeton University]) died in September of 1757.

Five months later, his grandfather (America’s greatest theologian, Jonathan Edwards) died.

Two weeks after that, his mother (Esther Edwards Burr) died at the age of 26.

And then in the fall of 1758, his grandmother (Sarah Edwards) died.

At the age of two, Aaron was an orphan.

As he grew older, he sadly abandoned the faith of his parents and grandparents.

Of all the notable people in the Burr family, it may be Esther who is most neglected. But there are signs that may be changing. For example, she is one of the women featured in Michael Haykin’s new book, Eight Women of Faith.

Thomas Kidd has quoted Ann Braude’s comment that “women’s history is American religious history.” Kidd writes:

For debated reasons, women have formed the majority within almost all American religious movements, including evangelical Christianity.

Yet in the study of church history, women remain largely in the background, if not altogether silent.

Some of this neglect originates with the difficulty of documenting the religious lives of American women. Pastors and theologians—mostly men—have been the most likely to leave published records behind, and especially in the colonial and Revolutionary eras, sources from women are few and far between.

Esther Burr is an exception to this rule. In 1986, Yale University Press published a critical edition of three years’ worth of letters she wrote as an adult to her friend Sarah Prince (1728-1771), which gives us a rare, unfiltered, inside look at female colonial American piety and a young life devoted to “sincere religion” and committed to “faithful friendship” (to use the description of Roger Lundin and Mark Noll).

In the letters Esther’s sharp wit and formidable intellect shine through. For example, she recounts one occasion when a tutor at the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University)—where her husband served as president—confidently asserted that women did not know “what Friendship was,” as “they were hardly capable of anything so cool and rational as friendship” (Letter No. 3, April 12, 1757).

Esther tells Sarah, “I retorted several severe things upon him before he had time to speak again. He blushed and seemed confused. . . . We carried on the dispute for an hour—I talked him quite silent.”

The tutor was out of his league, mocking a subject near and dear to Esther’s heart. She wrote about it both passionately and frequently to Sarah Prince.

In reading chronologically through her extant letters, I see several themes emerge for her working theology and practice of friendship.

1. Christian friendship is a gift from God that is preserved by God.

After Esther’s death, Sarah Prince wrote that Esther “was dear to me as the Apple of my Eye—she knew and felt all my Griefs. She laid out herself for my good and was every assiduously studying it. The God of Nature had furnished her with all that I desir’d in a Friend.” Sarah here focuses upon Esther’s exemplary acts of true friendship, involving empathy, sacrifice, and knowledge—all seen as a kindness from God in fulfilling the desire of Sarah’s heart.

As for Esther, she recognized the same, writing: “Once more I am allowed to call you friend, which I hope I am thankful for. Tis God that gives us friends, and he that preserves the friendship he has graciously begun.” To be sure, Christian friendship is not something that she took for granted: “‘Tis . . . a great mercy that we have any friends—What would this world be without ‘em—A person who looks upon himself to be friendless must of all Craetures be miserable in this Life—Tis the Life of Life” (January 23, 1756).

2. Christian friendship is rare and fragile but ultimately eternal.

After one of her best friends in town nearly dies, Esther writes to Sarah that “It really seems as if the time was come when friendship is going out of the World by one means or other, those that are formed for it taken away by death or threatened” (October 12, 1754; November 12, 1754). Esther recognizes that circumstances often conspire to threaten the preciousness of friendship. This was especially true on the early American frontier, where average life expectancy did not go beyond the thirties.

But the ultimate origin of Christian friendship, Esther reasons, indicates its true duration: “True friendship is enkindled by a spark from Heaven, and heaven will never suffer it to go out, but it will burn to all Eternity” (February 15, 1755).

3. Christian friendship expresses the language of affection.

Over and over again in her letters, Esther addresses Sarah with tender terms of endearment and appreciation. She frequently signs off, “I am, my dear friend, your most affectionate Friend and Sister” (March 6, 1756; November 21, 1754; June 14, 1755; April 17, 1756). She nicknames Sarah her “dear affectionate Fidelia” (October 17, 1756), that is, faithful or loyal one. Sarah, she says, is “my best self” (May 8, 1756), “the Sister of my heart” (October 11, 1754), “my ever dear friend” (December 25, 1754), “my beloved friend” (April 19, 1755). Signing one letter, “your unfeigned and very Affectionate Friend” (February 9, 1755), it is clear there were no restraints on their affection.

4. Christian friendship is a form of love.

This point is related to the previous one, but somewhat distinct. Modern readers are sometimes taken aback by the way in which same-sex friendships were described with passionate expression usually reserved for lovers. Our fear of homoerotic overtones has almost entirely muted this sort of language today. But it was common in Puritan New England and continued at least into the late nineteenth century, applying not only to friendships between women but also friendships between men.

For example, Esther describes how excited she would become at the arrival of a new letter from her friend: “I could not help weeping for joy to hear once more from my dear, very dear Fidelia. . . . I broke it open with [as] much eagerness as ever a fond lover embraced the dearest joy and delight of his soul” (March 7, 1755).

She felt similarly after having read the letter itself: “Every Letter I have from you raises my esteem of you and increases my love to you—their is the very soul of a friend in all you write—You cant think how those private papers make me long to see you” (Letter No. 21, April 16, 1756).

Esther even wonders at times if her love for Sarah is bordering on idolatry, becoming too attached to things of this earth: “As you say, I believe tis true that I love you too much, that is I am too fond of you, but I cant esteem and value too greatly, that is certain—Consider my friend how rare a thing tis to meet with such a friend as I have in my Fidelia—Who would not value and prize such a friendship above gold, or honor, or any thing that the World can afford? . . . I am trying to be weaned from you my dear, and all other dear friends, but for the present it seems vain—I seem more attached to ‘em than ever— . . .” (June 4, 1755). She sees friendship as one of life’s greatest earthly goods, though less than God.

5. Christian friendship can strengthen our relationship with God.

One of the things Esther most valued in her friendship was the sense of honesty and free transparency before a fellow pilgrim: “I think it is one of the great essentials of friendship [that] the parties tell one another their faults, and when they will [say] it and take it kindly it is one of the best evidences of true friendship, [I] think” (November 1, 1754).

A true friend is a confidant, a sounding board, one who can hear our true hearts and still love us: “I should highly value (as you my dear do) such charming friends as you have about you—friends that one might unbosom their whole soul too” (April 20, 1755).

Earlier we noted her fear of idolatry with friendship. But she also sees Christian friendship as a genuine godly pleasure: “Nothing is more refreshing to the soul (except communication with God himself), than the company and society of a friend.” In fact, she writes, “I esteem religious Conversation one of the best helps to keep up religion in the soul, excepting secret devotion, I don’t know but the very best—Then what a lamentable thing that tis so neglected by Gods own children” (April 20, 1755).

Esther Edwards Burr lived a short life, but she left with us a remarkable example of godly Christian friendship and thoughtful theological reflection on this gift of grace. It is tempting to speculate how her son’s life may have been different if he had known her, observed her example, and been shepherded by her through his formative years.