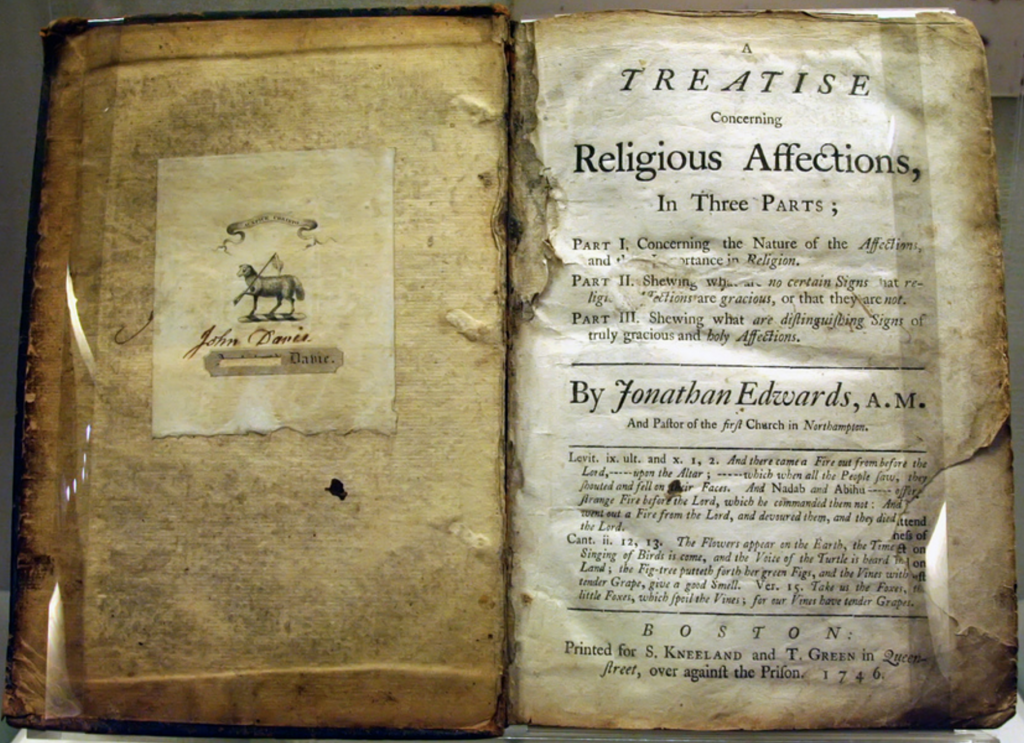

Jonathan Edwards’s A Treatise Concerning the Religious Affections (1746) is considered one of the great classics of evangelical literature.

(You can access the entire critical edition from Yale University Press online for free.)

Here is a brief overview.

What is the thesis of the book?

“True religion, in great part, consists in holy affections” (95).

What did Edwards mean by “affections”?

Edwards understood the human soul to have two faculties:

- the understanding (by which the soul perceives, speculates, discerns, views, judges things); and

- the inclination or will (by which the soul is inclined or disinclined, pleased or displeased, approves or rejects).

The affections have to do with the second faculty.

Affections, according to Edwards, are “the more vigorous and sensible exercises of the inclination and will of the soul” (96).

Edwards scholar Gerald McDermott explains it like this: affections are “strong inclinations of the soul that are manifested in thinking, feeling, and acting.”

What is the difference between an “emotion” and an “affection”?

Affections are more than emotions, though not less.

McDermott explains that affections are “strong inclinations that may at times conflict with more fleeting and superficial emotions.” He summarizes the differences like this:

| Affections | Emotions |

| Long-lasting | Fleeting |

| Deep | Superficial |

| Consistent with beliefs | Sometimes overpowering |

| Always result in action | Often fail to produce action |

| Involve mind, will, feelings | Feelings (often) disconnected from the mind and will |

Here is how Sam Storms explains the difference:

Certainly there is what may rightly be called an emotional dimension to affections. Affections, after all, are sensible and intense longings or aversions of the will. Perhaps it would be best to say that whereas affections are not less than emotions, they are surely more.

Emotions can often be no more than physiologically heightened states of either euphoria or fear that are unrelated to what the mind perceives as true.

Affections, on the other hand, are always the fruit or effect of what the mind understands and knows. The will or inclination is moved either toward or away from something that is perceived by the mind.

An emotion or mere feeling, on the other hand, can rise or fall independently of and unrelated to anything in the mind.

One can experience an emotion or feeling without it properly being an affection, but one can rarely if ever experience an affection without it being emotional and involving intense feelings that awaken and move and stir the body. (p. 45)

Are the affections essential to godliness, according to the Bible?

Edwards answers:

They would deny that much of true religion lies in the affections, and maintain the contrary, must throw away what we have been wont to own for our Bible, and get some other rule, by which to judge of the nature of religion (106).

Are all affections good?

No. Some are to be rejected and put to death while others are to be approved and cultivated. “The right way,” according to Edwards, is:

not to reject all affections,

nor to approve all;

but to distinguish between affections, approving some, and rejecting others; separating between the wheat and the chaff, the gold and the dross, the previous and the vile. (121; my emphasis)

In his book, Edwards is attempting to help readers in this distinguishing, approving, and rejecting task.

What are some of the uncertain or insufficient signs of truly gracious affections?

In the second part of the book, Edwards works through twelve “signs” that are uncertain. These things that may look like indicators of truly gracious affections, but which do not prove things one way or the other:

- The affections are very great, or raised very high. (127–31)

- The affections have great effects on the body. (131–35)

- The affections cause those who have them, to be fluent, fervent and abundant, in talking of the things of religion. (135–37)

- Persons did make the affections themselves, or excite them of their own contrivance, and by their own strength. (138–42)

- The affections come with texts of Scripture, remarkably brought to the mind. (142–45)

- There is an appearance of love in the affections. (146–47)

- Persons having affections of many kinds, accompanying one another, is not sufficient to determine whether they have any gracious affections or no. (147–51)

- Comforts and joys seem to follow awakenings and convictions of conscience, in a certain order. (151–63)

- The affections dispose persons to spend much time in religion, and to be zealously engaged in the external duties of worship. (163–65)

- The affections much dispose persons with their mouths to praise and glorify God. (165–67)

- The affections make persons that have them, exceedingly confident that what they experience is divine, and that they are in a good estate. (167–81)

- The outward manifestations of the affections, and the relation persons give of them, are very affecting and pleasing to the truly godly, and such as greatly gain their charity, and win their hearts. (181–90)

What are the signs or marks of true, gracious religious affections?

Then in the third part, Edwards sets forth twelve true signs—those things which distinguish the truly gracious and holy affections as being part of true religion:

- True religious affections arise from those influences and operations on the heart, which are spiritual, supernatural, and divine. (197–239)

- True religious affections are objectively grounded in the transcendently excellent and amiable nature of divine things, as they are in themselves (and not in any conceived relation they bear to self or self-interest). (240–52)

- True religious affections are primarily founded on the loveliness of the moral excellency of divine thing; a love to divine things for the beauty and sweetness of their moral excellency is the first beginning and spring of all holy affections. (253–65)

- True religious affections rise from the mind’s being enlightened, rightly and spiritually, to understand or apprehend divine things. (266–90)

- True religious affections are attended with a reasonable and spiritual conviction of the judgment, of the reality and certainty of divine things. (291–310)

- True religious affections are attended with evangelical humiliation (= a sense that a Christian has or his own utter insufficiency, despicableness, and odiousness, with an answerable frame of heart). (311–39)

- True religious affections are attended with a change of nature. (340–43)

- True religious affections tend to, and are attended with, the lamblike, dovelike spirit and temper of Jesus Christ; they naturally beget and promote such a spirit of love, meekness, quietness, forgiveness, and mercy, as appeared in Christ. (344–356)

- True religious affections soften the heart and are attended to and followed with a Christian tenderness of spirit. (357–64)

- True religious affections have beautiful symmetry and proportion. (365–75)

- With true religious affections, the higher gracious affections are raised, the more is a spiritual appetite and longing of soul after spiritual attainments increased. (376–82)

- True religious affections have their exercise and fruit in Christian practice. (383–462)

What books give help in unpacking the arguments of this book?

Here are two popular-level expositions of Edwards’s great work:

- Sam Storms, Signs of the Spirit: An Interpretation of Jonathan Edwards’ “Religious Affections”

- Gerald McDermott, Seeing God: Jonathan Edwards and Spiritual Discernment

For wider historical context, see Thomas Kidd’s The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America.