God promised Abr(ah)am a son in his old age, and then elaborated that the promised son would come from his wife Sarai, now Sarah, a promise that made both Abraham and Sarah laugh. I have heard a multitude of sermons over the years on Sarah’s laughter (generally casting it in a negative light – occasionally feminine weakness contrasted with Abraham’s faith). God’s promise and delivery of a son for Abraham by Sarah is a turning point in the biblical story, and one worth a careful look.

Our slow meander through the book of Genesis continues with a look at the several incidents were the Lord promises to make Abr(ah)am a mighty and populous nation. The promise is first stated in Genesis 12:2-3 repeated in v. 7 in broad sweeping terms. After the sojourn in Egypt, separation from Lot, and rescue of Lot and others from Sodom and Gomorrah, God comes to Abram again, this time in a vision. This is where we pick up the story today.

After this, the word of the Lord came to Abram in a vision:

“Do not be afraid, Abram.

I am your shield,

your very great reward.”

But Abram said, “Sovereign Lord, what can you give me since I remain childless and the one who will inherit my estate is Eliezer of Damascus?” And Abram said, “You have given me no children; so a servant in my household will be my heir.”

Then the word of the Lord came to him: “This man will not be your heir, but a son who is your own flesh and blood will be your heir.” He took him outside and said, “Look up at the sky and count the stars—if indeed you can count them.” Then he said to him, “So shall your offspring be.”

Abram believed the Lord, and he credited it to him as righteousness. (15:1-6)

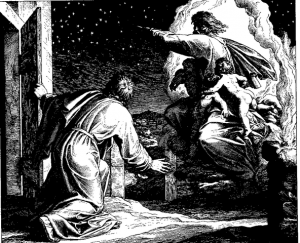

This is followed by a promise concerning the land, backed up by a covenant between Abram and the Lord. An interesting ritual with Abram preparing sacrificial animals and the a smoking firepot and blazing torch passing between them signifying the Lord’s covenant promise to Abram. This incident is interesting and worth discussion, but not the focus of our post today.

Studies of ancient Near Eastern culture shed light on this passage. Bill Arnold (Genesis) suggests that prior to the separation of Lot and Abram, Lot was the heir apparent. Now, however, Abram and Sarai cannot count on Lot to care for them in old age. As a result, a servant of the household is heir providing he care for the couple as they age. Arnold along with Tremper Longman (Genesis) and John Walton (NIVAC Genesis) note that this was an accepted practice in the ancient Near East as a protection for the childless couple. Eliezer of Damascus was trusted, traveling with, and serving Abram and Sarai.

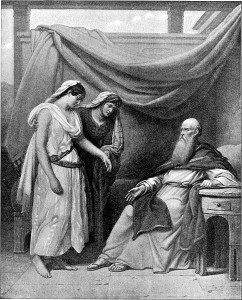

A son from a maid servant. In Genesis 16 we read the strange (to our ears) story of Sarai, Hagar and Ishmael. Although it is popular in Christian circles to discuss the shortcomings of Abram and Sarai here, how they failed to trust God and took matters into their own hands, this isn’t really a fair reading of the text or a fair evaluation of the situation. Thus far the promise of a son for Abram hasn’t included Sarai as the biological mother. It was accepted practice in the culture to give a servant as a concubine to bear a child when the wife was barren. Arnold, Longman, and Walton all make this point. C. Leonard Woolley in The Sumerians comments:

A barren wife could be divorced, taking back her dowry and receiving a sum of money by way of compensation; otherwise the husband could take a second wife, but in that case he not only continued to be responsible for the maintenance of the first but had to safeguard her position in the home; the new wife was legitimate, but not the equal of the old, and a written contract defined the degree of her subservience, thus she might be obliged to ‘wash the feet of the first and to carry her chair to the temple of the god.’ In practice, however, the status of the two women must have been somewhat anomalous, and to forestall this the wife might present to her husband one of her own slaves as a concubine; on giving birth to a child the slave-woman automatically became free … but was by no means the equal of her old mistress; indeed, should she rashly aim at becoming her rival, the mistress could again reduce her to slavery and sell her or otherwise get rid of her from the house. (p. 102-103)

Taking a second wife is never mentioned in the story of Abraham, but the practice of giving a concubine to bear children is seen in the story of Hagar and Sarah and in the story of Jacob and his twelve sons. In fact, the story of Hagar and Ishmael follows well established procedures. As John Walton points out, Sarai may be “invoking the terms of her marriage contract” as existing examples of contracts specify the giving of a maid servant and even the dispensing of the servant (and presumably the child) if the wife later produces an infant for her husband.

Based on the word of the Lord to Abram thus far, and the culture of the time, Ishmael was a legitimate heir and “a son who is your own flesh and blood.” Unless there was some revelation to Abram we don’t know, he wasn’t second guessing God or rushing the matter. This isn’t to say that all behavior related in this incident was honorable. None of the principles are blameless – Hagar in her pride, Sarai in her jealousy, or Abram in his failure to uphold Sarai before it got so far.

The promise brings laughter. In Genesis 17 the Lord appears to Abram again and makes the covenant more clear – Abram, now renamed a slight variant Abraham, “will be the father of many nations.” Circumcision (a common practice in the ancient Near East, although not infancy) is given theological importance as a sign of the covenant between God and his people. Abraham is specifically told that Sarai, now Sarah will give birth to a son, and this is the son of the promise.

Abraham fell facedown; he laughed and said to himself, “Will a son be born to a man a hundred years old? Will Sarah bear a child at the age of ninety?” And Abraham said to God, “If only Ishmael might live under your blessing!”

Then God said, “Yes, but your wife Sarah will bear you a son, and you will call him Isaac. I will establish my covenant with him as an everlasting covenant for his descendants after him. And as for Ishmael, I have heard you: I will surely bless him; I will make him fruitful and will greatly increase his numbers. He will be the father of twelve rulers, and I will make him into a great nation. But my covenant I will establish with Isaac, whom Sarah will bear to you by this time next year.” When he had finished speaking with Abraham, God went up from him. (17:17-22)

Abraham laughed at the idea that he and Sarah would have a son. He was also concerned for his first born son and God promises Abraham as he promised Hagar in Genesis 16 that Ishmael would be blessed.

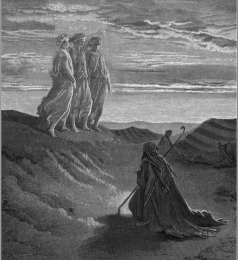

Finally we have the popular story of the three visitors in Genesis 18:1-15. Abraham prepares a feast for the three travelers, to a level that went beyond common hospitality, about 36 pounds of flour to make bread, a choice tender calf, and curds and milk.

Finally we have the popular story of the three visitors in Genesis 18:1-15. Abraham prepares a feast for the three travelers, to a level that went beyond common hospitality, about 36 pounds of flour to make bread, a choice tender calf, and curds and milk.

Now it was Sarah’s turn to laugh.

Then one of them said, “I will surely return to you about this time next year, and Sarah your wife will have a son.”

Now Sarah was listening at the entrance to the tent, which was behind him. Abraham and Sarah were already very old, and Sarah was past the age of childbearing. So Sarah laughed to herself as she thought, “After I am worn out and my lord is old, will I now have this pleasure?”

Then the Lord said to Abraham, “Why did Sarah laugh and say, ‘Will I really have a child, now that I am old?’ Is anything too hard for the Lord? I will return to you at the appointed time next year, and Sarah will have a son.”

Sarah was afraid, so she lied and said, “I did not laugh.”

But he said, “Yes, you did laugh.” (18:10-15)

In Genesis 21:1-7 the promise comes true when Isaac was born. God brought a pleasant laughter to Sarah and to Abraham. Hagar and Ishmael are sent away … not in the best of ways or on good terms … but God protects and blesses Ishmael as well.

Sermons, Sunday school lessons, and Bible studies. Along with most other Christians, especially those in the church from childhood, I have heard many sermons and lessons on these passages in Genesis. A fair number of them have missed the point in one fashion or another. It is common to emphasize Abraham’s faith (15:6) and Sarah’s laughter (18:12). But I can’t remember a sermon or lesson where Abraham’s laughter was mentioned alongside Sarah’s. Both of them laughed at the idea of a child at their (especially her) age. Whether they were really 90 and 100 years old when Isaac was born is unimportant (I tend to think the ages are symbolic exaggeration as numbers often are in the Old Testament). Sarah was barren and past the normal age for bearing a child. To emphasize Sarah’s laughter misses the point.

Likewise, sermons and lessons that focus on the impatience of Abram and Sarai, their failure to trust the promise of God by turning to Hagar to bear a son reads our expectations back into the text. Human nature is such that the practice causes trouble, but not substantially more than the trouble caused by barrenness and the lack of offspring. I tend to think that Ishmael, and the twelve rulers from his descendants, are part of God’s plan of eventual blessing for the entire world. This isn’t a plan B tacked on because Abram and Sarah jumped the gun. How it all works out, we are not told. “Note that God’s care for Ishmael and his descendants is motivated by his relationship with Abraham, illustrating that blessing comes not just to the so-called elect line, but also to other nations.” (Longman p. 273) Later: “At a minimum, the fact that God is with Ishmael again shows that God does not have contempt but rather love for the nonelect offspring of the patriarchs and those nations that ultimately derive from them.” (Longman p. 274)

Likewise, sermons and lessons that focus on the impatience of Abram and Sarai, their failure to trust the promise of God by turning to Hagar to bear a son reads our expectations back into the text. Human nature is such that the practice causes trouble, but not substantially more than the trouble caused by barrenness and the lack of offspring. I tend to think that Ishmael, and the twelve rulers from his descendants, are part of God’s plan of eventual blessing for the entire world. This isn’t a plan B tacked on because Abram and Sarah jumped the gun. How it all works out, we are not told. “Note that God’s care for Ishmael and his descendants is motivated by his relationship with Abraham, illustrating that blessing comes not just to the so-called elect line, but also to other nations.” (Longman p. 273) Later: “At a minimum, the fact that God is with Ishmael again shows that God does not have contempt but rather love for the nonelect offspring of the patriarchs and those nations that ultimately derive from them.” (Longman p. 274)

God’s covenant follows Isaac. Ishmael isn’t abandoned by God, but Isaac and his descendants through Jacob are God’s elect people. Isaac’s birth is significant. Isaac is not only the result of natural biological processes, but specifically the result of the promise of God superseding the natural. Sarah was past the age of child bearing, yet as promised she bore the child of the covenant. Through the birth of this son God’s mission in the world was made clear. Tremper Longman comments “the birth at this “appointed time” clearly demonstrates that this child is not simply the result of natural human processes, but is rather a divine gift.” (p. 271-272)

The prediction of the birth of Isaac, the fact that this was an unusual birth, all this helps confirm the hand of God in Abraham, Sarah and their descendants. This is, in many respects, the heart of Genesis.

What significance should we attach to the birth of Isaac?

How have you heard this story taught?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.