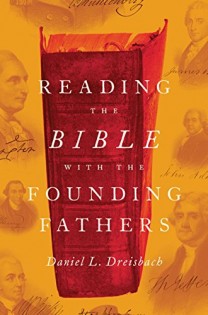

American University professor Daniel Dreisbach is probably the foremost expert on religion in the American founding era and a devoted student of the Bible, so he’s arguably the best person to write a book on the Bible’s use during that period. Indeed, Reading the Bible with the Founding Fathers is a tour de force of scholarly research.

Dreisbach produces hundreds, perhaps thousands, of clear or subtle references to Bible verses by public persons in America between 1760 and 1800. His goal is to demonstrate that “the Bible was important to the social, legal, and political thought of the founding generation and a vital influence on the culture in which they lived” (6). His other stated goal is to “combine credible historical research and careful textual analysis with basic biblical scholarship and political theory” (16).

In the “Introduction” and the “Afterword,” Dreisbach establishes some very important caveats. First, the founding generation “drew on multiple sources” of influence, and the Bible didn’t necessarily supersede the rest. Second, a founder’s use of the Bible “does not indicate whether he or she was a Christian or a skeptic,” as both used the Bible for their own purposes. Third, a claim of biblical influence “does not suggest that the founders were theocrats intent on imposing a biblical order.” Fourth, the “mere fact that the founding generation frequently quoted from and alluded to the Bible reveals little about the American founding or the Bible’s influence on late 18th-century political thought, except that the Bible was a familiar and useful literary source.”

In light of these cautionary notes, Dreisbach warns against a “mere quantitative accounting of biblical references” and emphasizes the need to “be attentive to the purposes for which biblical texts were invoked,” the historical context of their use, the biblical context of passages, and the proper interpretation of verses (6–8). All of these are valuable and crucial insights to remember when reading this book or one like it.

Interpreting the Patriots’ Interpretations

Dreisbach demonstrates the ubiquitous presence of the Bible in the discourse of the day. He makes a decided effort to provide biblical context for verses and to lay “traditional” or “conventional” (i.e., literal) interpretations alongside those devised and employed by the founding generation. He does the latter with mixed success. Sometimes he brings the original Hebrew or Greek into his analysis; sometimes he doesn’t. He devotes special sections to examine context and interpretation of certain passages; for others, he gives no such evaluation. For the most part, these special sections are quite good, although he fails to point out that passages from the book of Proverbs are proverbs—not God’s promises, invariable rules, or “oaths of God” as the “patriots” took them (e.g., 17, 174). Like the patriots, Dreisbach also tends to cite God’s covenants with and promises to his chosen people, Israel, as if they are universally applicable.

Dreisbach allots about three general paragraphs to the “conventional” (i.e., literal, direct) interpretation of Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2—passages that “on their face” disallow resistance to authority and had been generally understood that way for more than 1,500 years. On the other hand, he devotes an entire chapter to a creative interpretation favored by the American patriots and its historical—largely nonbiblical—genesis. Indeed, there’s scarcely a word from the Bible for 20 pages (116–135), but there’s a lot of history and political theory. Dreisbach calls this interpretation—one that relies heavily on adding words and ideas to Romans 13—a “nuanced” interpretation, and commends the work of one of its creators for its “refreshing acquaintance with political thought in the Scripture” and presentation of a “cogent” theory (124). This would be understandable in a generic study of the political thought of the founding generation, but it’s problematic in a study that specifically expresses concern for biblical context and proper interpretation of Scripture.

Dreisbach obviously had to explain the interpretation of passages used to promote the American Revolution, but a truly biblical analysis of this issue would seem to require addressing the problems and inconsistencies inherent in rejecting the literal, direct interpretation in its historical and biblical context.

In the Hands of the ‘Founders’

Another concern arises regarding Dreisbach’s identification of some Bible use by the founding fathers. By his own account, his “expansive” definition of “founding fathers” includes “an entire generation or two of Americans” and “a cast of thousands” (12). One wonders who’s not a founding father and, consequently, what significance is left to the term. Indeed, much of the Bible usage in Part II (the last 140 pages or so) is from preachers in sermons—not by actual revolutionary leaders or leading political figures creating the new nation’s Constitution and institutions. With the exception of George Washington, few generally held to be “founding fathers” have more than a token presence in the book. A more appropriate title might be “Reading the Bible with the Founding Generation.”

One critical question hangs over the volume: Did the Bible influence the “founding fathers” or did they simply find it useful for illustrating and bolstering their own ideas gleaned from other sources? The Bible’s use throughout the founding era, and especially the revolutionary period, suggests the latter. For example, despite claims that the book of Deuteronomy and the example of the Hebrew commonwealth provided “principles, models, and precedents useful to them in the creation of their own polities,” the framers didn’t re-create the structures, institutions, or processes of that system (66). They simply sanctified their own novel and unprecedented system by claiming it followed a biblical example.

Despite these concerns, Reading the Bible with the Founding Fathers is a valuable cultural contribution. As long as one applies Dreisbach’s own cautionary notes in drawing conclusions, there’s much to be learned. An attentive reader might discover that biblical literacy was far more extensive in the founding era than today, which made both appropriate and inappropriate use of Scripture a powerful tactic of promoters of political causes. Since biblical stories and individual verses were, like today, better known among the people than proper hermeneutical principles, abuse of the Bible often ran parallel to use of the Bible.

‘Reading the Bible with the Founding Fathers’ is a must-read for those interested in religion during the American founding period, but read it with a critical eye.

Daniel Dreisbach. Reading the Bible with the Founding Fathers. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. 334 pp. $34.95.