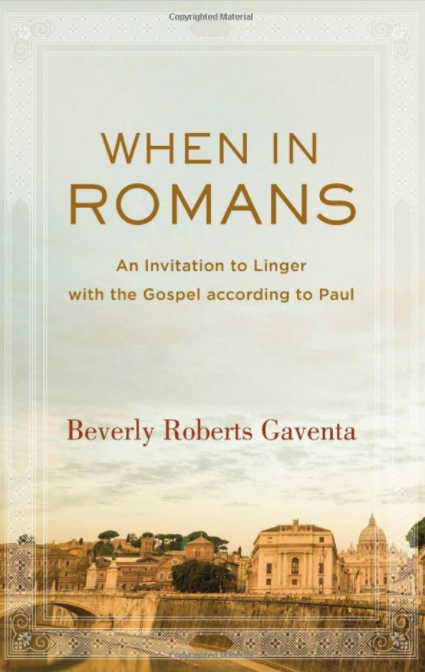

Beverly Gaventa has become an increasingly, patient and influential voice in Pauline studies. My favorite book of hers so far on Paul is Our Mother Saint Paul. A student and colleague of the architects of the apocalyptic scholars — like J. Louis Martyn and J. Christiaan Beker — Gaventa has been working on Romans most of her career and we are just beginning to get a glimpse of her forthcoming Romans commentary in her new book When in Romans.

Beverly Gaventa has become an increasingly, patient and influential voice in Pauline studies. My favorite book of hers so far on Paul is Our Mother Saint Paul. A student and colleague of the architects of the apocalyptic scholars — like J. Louis Martyn and J. Christiaan Beker — Gaventa has been working on Romans most of her career and we are just beginning to get a glimpse of her forthcoming Romans commentary in her new book When in Romans.

Here are some questions for her and her answers:

What is the significance of Phoebe (16:1-2) and her relationship to the letter?

I content that Phoebe is the earliest interpreter of Romans. She is the one who delivers the letter, as seems obvious. I think she is also the best candidate for the letter’s presenter (i.e., reader) in the Roman congregations. She is the one who would interpret it, either as she reads or in conversation after someone else read. It’s a bit hard to imagine that Paul dispatched this letter with her without having a long conversation about what he wanted to achieve, but finally she is the one who will answer questions, expand, defend or qualify.

You often ask your students to describe the letter to someone who has never read it. One common reply is it is about “sin, salvation, and sanctification.” Your concern with this reply is its “breeziness.” What do you mean by that?

Of course, Romans is about all those things, but it is about a great deal more. I characterize that trilogy as “breezy” because it often comes off the tongue too easily, without a lot of thought about what those terms mean, how they are at work in this letter, how this letter is like and unlike other texts in Scripture.

You say that “salvation” is a much more complex idea in Romans than we have imagined. In particular you say it is more “cosmic”. What is this “cosmic” dimension and how should it affect our reading of the letter? How does this view differ with the typical understanding of salvation as the opportunity for an individual to be eternally saved?

“Cosmic” doesn’t exclude reference to the individual’s relationship to God. I wouldn’t characterize that as an “opportunity,” since Paul talks about the individual relationship as one of “calling,” rather than “offer.” I think Paul does have a strong sense of God’s action in Jesus in the lives of individuals. But he also has a sense of the corporate—the social relationships within, across, and beyond believing communities.

“Cosmic” does not deny either of those dimensions to Paul’s thought. It includes them but takes into account also both the redemption of the whole of creation and the cosmic nature of the “problem” at hand. Romans 5-8 makes it clear that the human problem is not just belief or unbelief but human captivity to powers that are larger than human life, powers from which God’s action in Jesus is liberative (redemptive, salvific).

Paul makes little or no reference to repentance or forgiveness in Romans. Why is that important to Paul’s argument?

Precisely because the human problem, as Paul sees it, is larger than simply repenting and being forgiven, he casts the gospel in terms of redemption and salvation. In Romans 5 and 6, he speaks of Sin and Death ruling over humankind, even of humans as slaves to Sin. Slaves have to be set free; they cannot simply repent.

In your discussion of Paul’s ethics you state that our readings have been too restricted. You propose a better starting point for this discussion is to think about worship. Would you expand on that?

Here I take my starting point from Romans 1:18-32, noticing that the originating problem is the withholding of glory from God—worship! Because humans did not worship God rightly, they were “handed over,” resulting in the various behavior Paul castigates there. So, worship is at the heart of things. Importantly, worship is also featured in 12:1, the opening of the “ethical” section of the letter. There Paul uses liturgical language (the offering of the self as a right act of worship) to introduce his comments on various questions we call ethics. The two are so intertwined that we cannot take them apart, although our assumption is that they are separable.