December 9, 1812 is the birth date of James Henley Thornwell, the South Carolina Presbyterian pastor and professor whom Eugene Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese called the antebellum South’s “most formidable theologian.” Thornwell was a great champion of what he called the “regulated freedom” of antebellum slave society.

Historian George Bancroft once described Thornwell as “the most learned of the learned,” the epitome of the antebellum southern gentleman theologian. He graduated from South Carolina College at nineteen, and studied briefly at Harvard Divinity School. But not relishing northern culture or Harvard’s theology, he returned to his home state and became a Presbyterian minister. In 1837 he married Nancy Witherspoon, a great-niece of the celebrated Princeton president John Witherspoon.

He also taught at South Carolina College (the future University of South Carolina), and in 1851 became its president. Thornwell staunchly defended biblical orthodoxy, but also sought to harmonize new scientific learning with the faith. For instance, Thornwell (like many conservative Protestants of the era) argued that Christians could reconcile the apparent old age of the earth with the ‘days’ of Genesis 1 by interpreting the days as longer periods of time.

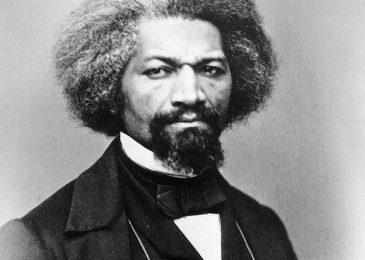

James Henley Thornwell

Most Christians today would struggle to reconcile Thornwell’s learned orthodoxy with his defense of slavery. Thornwell found no explicit condemnation of slavery in Scripture, only rules governing the behavior of slaves and masters, and he argued that Christians should go no further than Scripture in mandating moral codes. Thornwell was one of the chief advocates of the benevolent qualities of southern slaveowning, contrasting it with the brutal, chaotic northern factory system, in which owners had no responsibility whatsoever to workers.

For Thornwell, slaves were part of the Christian master’s “household,” which entailed great responsibilities to provide for the slaves’ physical, educational, and spiritual needs. Tragically, this ideology of slaveowning “paternalism” created “fatal self-deception” among its proponents, according to the Genoveses. Thornwell and others crafted a romanticized version of idyllic Christian plantations that papered over the ugly, exploitative realities of antebellum chattel slavery.

As the crisis between North and South grew more acute in the 1850s, theologians such as Thornwell became consumed with the grave threat they saw in the agenda of radical northern abolitionists, who they feared would pull out the props that had undergirded southern society since the colonial period. For proslavery southerners, the political controversy of the 1850s was not just about slavery vs. antislavery, but a matter of survival for the society they knew and loved.

In one of his most famous sermons, The Rights and the Duties of Masters (1850), Thornwell declared that “these are the mighty questions which are shaking thrones to their centres—upheaving the masses like an earthquake, and rocking the solid pillars of this Union. The parties in this conflict are not merely abolitionists and slaveholders—they are atheists, socialists, communists, red republicans, jacobins, on the one side, and the friends of order and regulated freedom on the other. In one word, the world is the battle ground—Christianity and Atheism the combatants; and the progress of humanity the stake.”

Once Lincoln — a representative of the new, exclusively northern Republican Party — assumed the presidency, the South had no other choice but to secede from the Union, or so Thornwell would argue in 1860. His home state of South Carolina led the way. Thornwell died of tuberculosis in August 1862, two weeks before the Battle of Antietam, when Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and the Confederate South still seemed ascendant.

Further reading on Thornwell and proslavery Christianity:

J.O. Farmer, The Metaphysical Confederacy: James Henley Thornwell and the Synthesis of Southern Values (1986)

This post originally appeared at the Anxious Bench blog.